From Lunar Distances to Radio Pulses: Engineering the Longitude of Sydney

Richard de Grijs

(School of Mathematical and Physical Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia)

The longitude of Sydney Observatory has been measured for more than 250 years, (see Sydney's Longitude), yet the numbers themselves tell only part of the story. Behind the apparent stability of the meridian lies a succession of engineering transformations: from lunar observations and chronometer transport, to telegraphic synchronisation across Asia in 1883–1884, to wireless time signals and later radio-navigation systems. Each technological shift dramatically reduced uncertainty—from kilometres to tens of metres. The history of Sydney’s longitude is therefore not primarily astronomical; it is infrastructural. Australian engineers and surveyors played a central role in building and operating the telegraphic and wireless networks that made precise, continental-scale time comparison possible. Longitude became not merely observed but engineered.

1. Measuring a Meridian

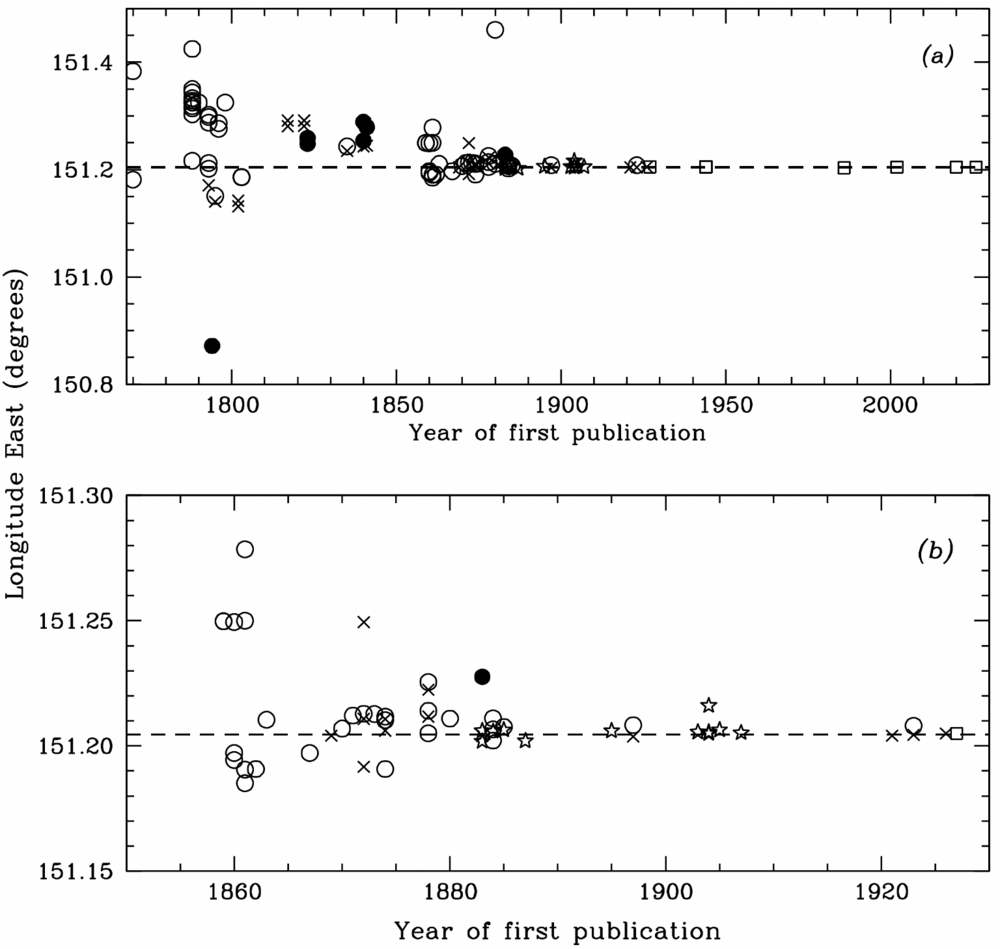

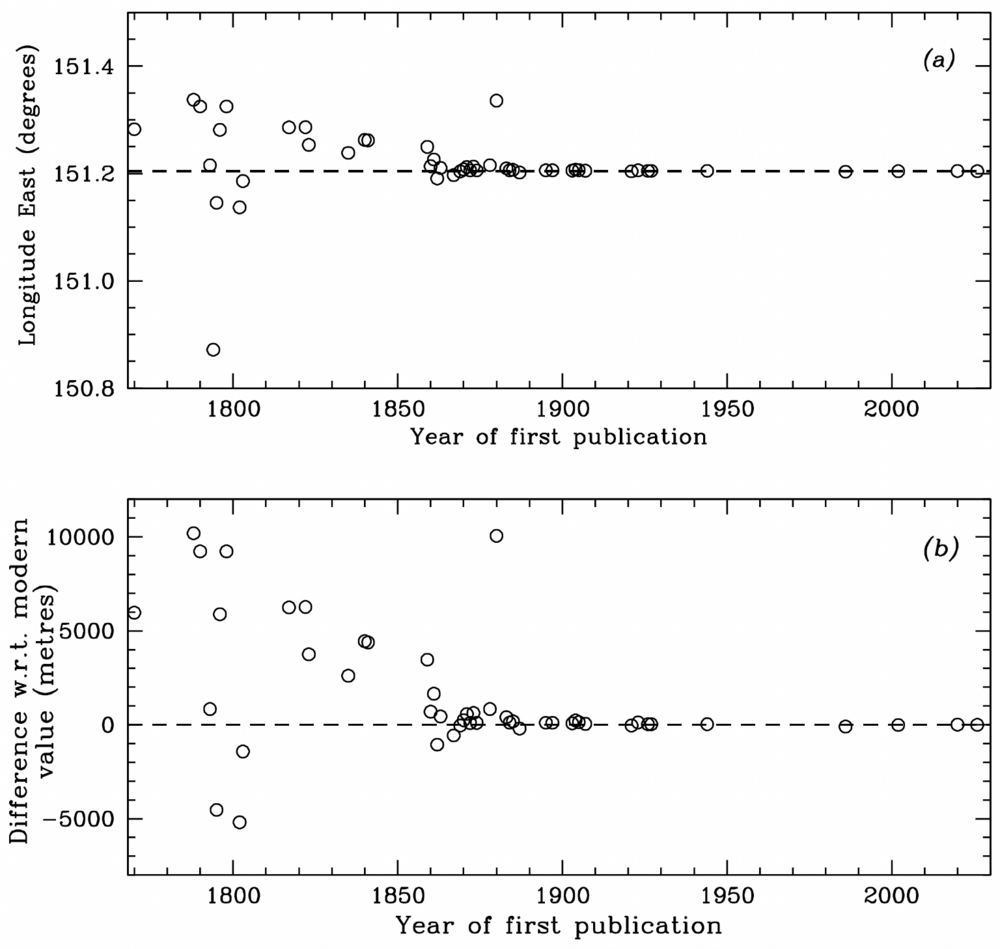

The longitude of Sydney Observatory has been determined repeatedly since the eighteenth century. At first glance, the numerical history appears uneventful: the meridian stabilised within a few seconds of time early on, and subsequent determinations differ only in decimals. Yet behind this apparent stability lies a profound transformation in measurement engineering. Longitude determination is fundamentally a timing problem. One hour of time corresponds to 15 degrees of longitude; one second of time equals 15 seconds of arc. At Sydney’s latitude, (33° 51' 34.47" South), one second of time corresponds to approximately 390 metres on the ground. A difference of only half a second therefore implies a positional shift of nearly 200 metres.

2. Astronomical Longitude

When James Cook landed in Botany Bay in 1770, he determined longitude by lunar distances. (See Lunar Distances) His value—later transposed to the Sydney meridian—was within a few seconds of modern coordinates, an extraordinary achievement given the instruments and lunar tables available at the time. However, the uncertainty envelope remained at kilometre scale.

Throughout the early nineteenth century, observatories at Parramatta and later Sydney refined the longitude using meridian transits and lunar culminations. These determinations depended on chronometer stability, reduction tables, meteorological conditions and the well-known physiological ‘personal equation’ of observers timing star transits by eye and ear. (See Personal Equation) Differences of two to four seconds of time—equivalent to one to two kilometres—were typical between independent reductions. Astronomical longitude determination was therefore a craft as much as a calculation. It required skilled observers, stable clocks and extensive post-observation analysis. Precision improved gradually, but dispersion remained measurable and persistent.

3. The Telegraphic Transformation

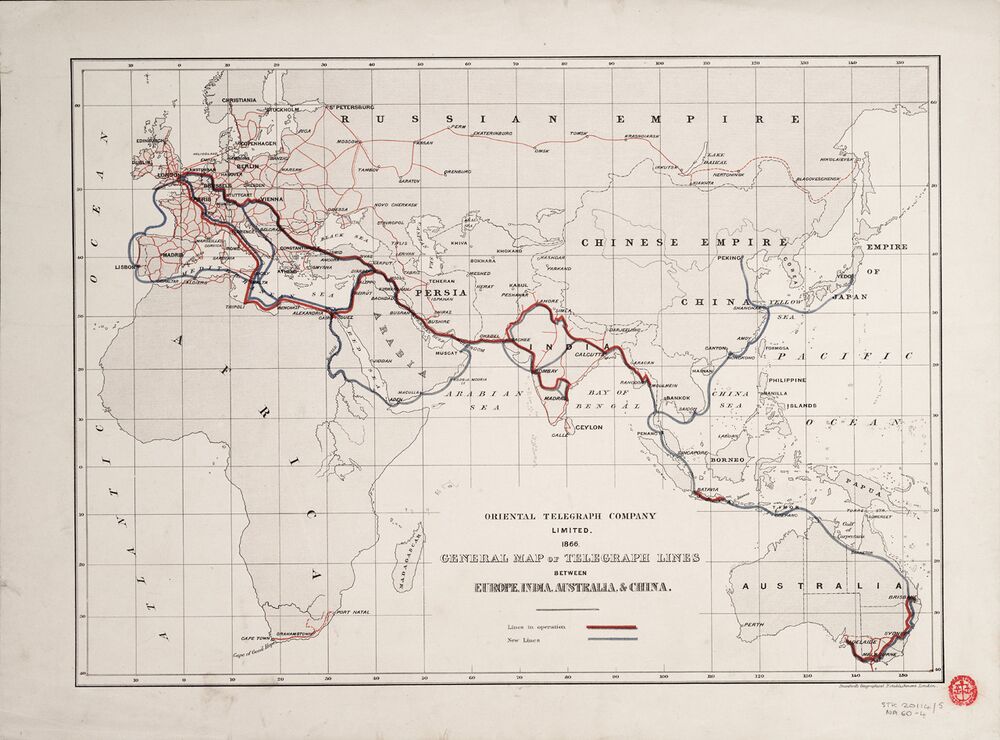

The decisive engineering shift occurred in 1883–1884, when Sydney was connected by telegraph through Port Darwin, Banjoewangie (Java) and Singapore. (See Telegraph) For the first time, clocks separated by thousands of kilometres could be compared electrically rather than by chronometer transport. Instead of transporting time physically across oceans, observers exchanged signals over cable and measured transmission intervals. Longitude was reduced to a problem of electrical timing and signal delay. The resulting determination—10h 04m 49.31s East—fell within a few tenths of a second of modern values.

The statistical effect is clear. Prior to telegraphy, published values varied by several seconds. After 1884, the spread collapses to tenths of a second—on the order of 40–80 metres spatially. The meridian itself did not move; the uncertainty envelope contracted dramatically. This moment represents the transition from observation-limited precision to infrastructure-limited precision. The telescope remained, but electrical synchronisation now dominated the error budget.

4. Wireless Synchronisation and International Time

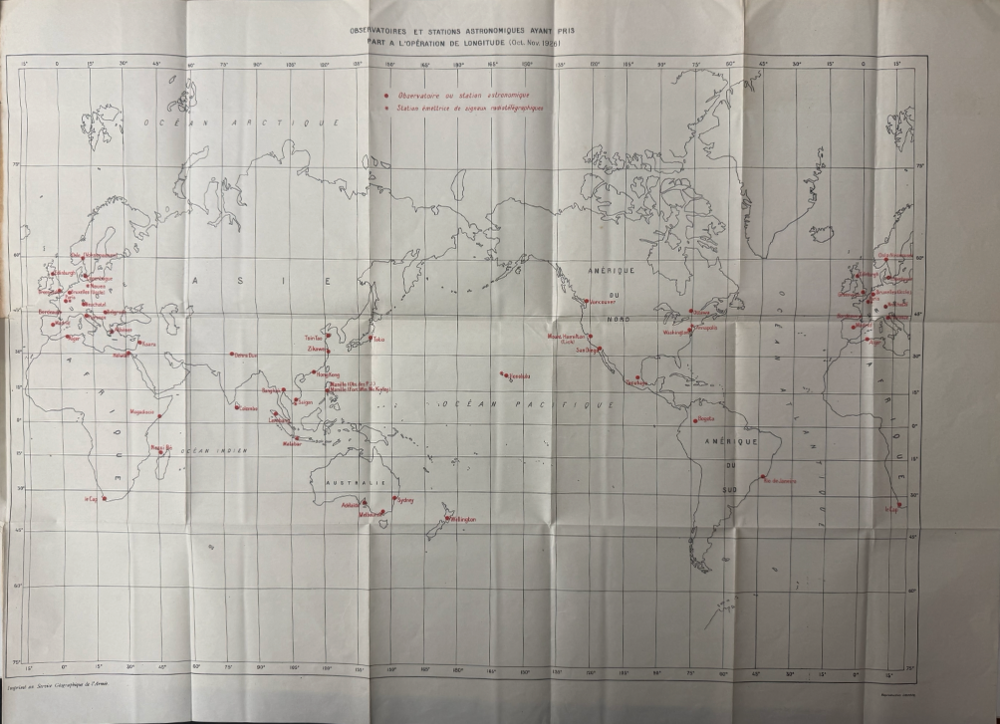

By the early twentieth century, wireless radio further changed the system. In 1921, longitude comparisons could be made via wireless time signals without reliance on fixed cable routes. (See Wireless)

The resulting corrections were small—fractions of a second—but they reflect a new expectation of precision. Differences that would have been negligible in the 1840s were now treated as significant. The engineering focus shifted from observational accuracy to signal propagation, timing protocols, and standardisation. Longitude had become embedded in global communication networks.

5. LORAN and the Engineering Break [1]

The introduction of LORAN (LOng RAnge Navigation) during the Second World War marked a structural break in the relationship between astronomy and navigation. Earlier telegraphic and wireless campaigns still relied on astronomical transit observations to anchor clocks. LORAN dispensed with celestial observation entirely. Position was determined by measuring the difference in arrival times of synchronised radio pulses from fixed transmitting stations. Navigators no longer required meridian circles, transit instruments or chronometers regulated to sidereal time. Instead, they relied on radio receivers and hyperbolic time-difference curves derived from signal geometry.

Even early LORAN accuracy—often hundreds of metres—operated comfortably within the precision envelope established by late nineteenth-century telegraphic longitude. The significance of LORAN was not that it immediately surpassed astronomical precision, but that it relocated authority from observatory domes to electronic transmitters. Longitude became an engineering output of synchronised networks.

6. Convergence and Stability

When the full, chronological sequence of determinations is considered, a clear pattern emerges. Early astronomical values vary by several seconds of time—equivalent to kilometres. After 1884, values cluster tightly within a few tenths of a second. Twentieth-century refinements adjust decimal places rather than whole seconds. The median value stabilises near 10h 04m 49s. There is no evidence of meridian drift; only progressive contraction of uncertainty. The transformation is not geographic but metrological.

In spatial terms:

• Early dispersion: ~1–2 km

• Telegraphic dispersion: <200 m

• Wireless and later geodetic refinements: <50 m

7. Datum and Geodetic Standardisation

Twentieth-century mapping introduced additional refinements through geodetic datums. Australian maps prior to 1966 relied on the Clarke ellipsoids (See Clarke) (1866 and 1880) within a transverse Mercator projection. (See Mercator) Later systems, including AGD66 (Australian Geodetic Datum 1966) and eventually GDA94/GDA2020 (Geocentric Datum of Australia 1994/2020), adjusted coordinates to reflect improved knowledge of Earth’s figure. (See Geocentric Datum of Australia)

These datum transformations typically introduce shifts comparable to late nineteenth-century astronomical uncertainties—tens of metres rather than kilometres. Again, the scale of change reflects refinement, not revision.

8. Engineering Perspective

From an engineering standpoint, the longitude of Sydney illustrates three successive regimes:

1. Astronomical determination — precision constrained by observation and reduction.

2. Electrical synchronisation — precision constrained by network timing and signal delay.

3. Radio navigation and geodesy — precision constrained by signal geometry and geodetic modelling.

Each regime reflects a different technical solution to the same fundamental problem: how to compare clocks separated by large distances. The most significant improvement occurred with the adoption of telegraphic infrastructure. That transition reduced uncertainty by an order of magnitude and established the framework within which modern positioning systems operate.

9. The Bottom Line

The story of Sydney’s longitude is ultimately a story of Australian engineering capability. The 1883–1884 telegraphic campaign linking Sydney through Port Darwin, Banjoewangie and Singapore was not simply an astronomical exercise; it was a continental-scale systems project. It required reliable submarine cables, repeater stations, timing protocols, signal calibration and disciplined coordination across colonial and international networks. Australian engineers and surveyors were central to its execution. Their work reduced positional uncertainty by an order of magnitude and integrated Australia into the emerging global time infrastructure.

Subsequent wireless campaigns and participation in international longitude revisions further demonstrated that Australia was not merely a peripheral recipient of metropolitan standards but an active contributor to global geodetic coordination. By the twentieth century, longitude determination in Sydney had become part of a worldwide engineering system of synchronised clocks, radio transmission, and standardised datums. The observatory dome remained fixed; what evolved around it was a layered infrastructure of cables, transmitters and geodetic models. In that sense, the meridian of Sydney marks a clear trajectory of engineering achievement.

Tabulated data and references.