Francis Webb Sheilds

Francis Webb Sheilds (1820 - 1906)

It is easy to overuse the adjective ‘amazing’, but a small book which in 2020 arrived as part of a bequest to the Australian Railway Historical Society (ARHSnsw) probably warrants the use of the term.

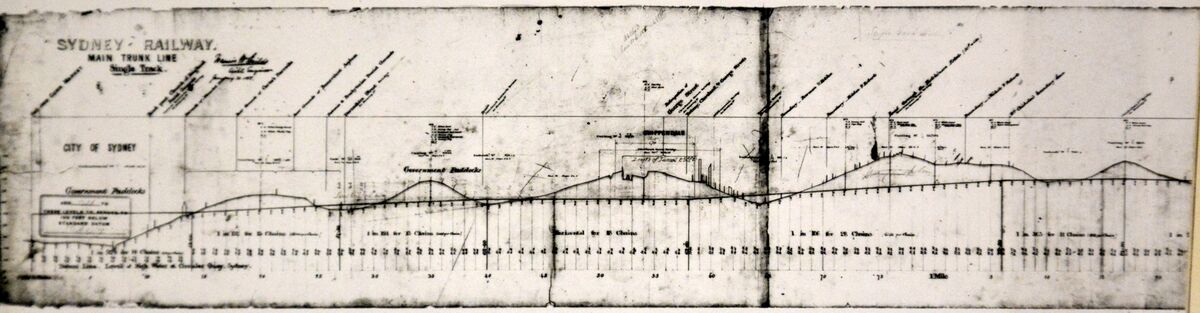

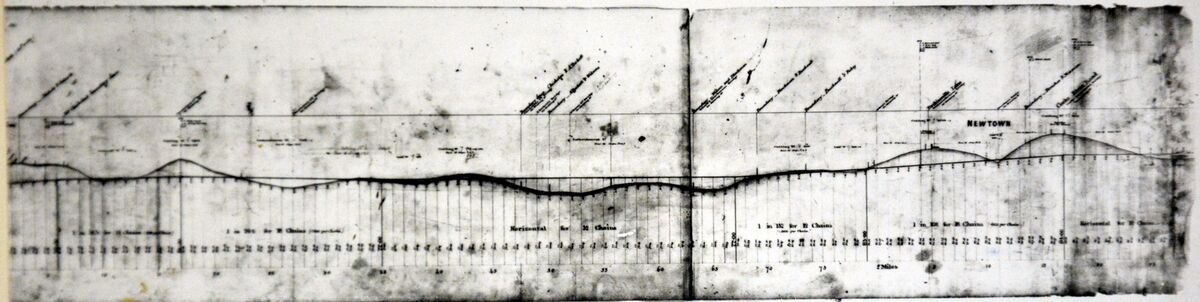

A small red cloth-covered book of only 56 pages titled The Strains on Structures of Iron Work, by F.W. Sheilds, may seem to be just another old textbook of structural mechanics, quaint in its terminology and simple in its analysis by later standards, until the reader realises the connection between Sheilds and Australia, particularly New South Wales. Francis Webb Sheilds was, in April 1848, the first engineer employed by the Sydney Railway Company. While his tenure did not extend to see the first railway operating, the present Main Suburban Line, from Sydney to Parramatta, remains on his selected alignment, and so a very large proportion of Sydney commuters traverse his route every day. Sheilds had been born in Ireland in 1820, though it is probably better to consider him to have been an Anglo-Irishman rather than an Irishman, for while the debate and debacle of railway gauge in Australia – Irish Gauge (5’3”, 1600mm) versus British Standard Gauge (4’8½”, 1435mm) – can be traced back to Sheilds, it would be simplistic to ascribe his recommendation to use the wider gauge as mere parochialism brought about by his place of birth.

Sheilds had worked in England as an engineer under Charles Vignoles, whose name is probably most quickly associated in the minds of engineers with the development of flat-bottomed rail which is now standard, but in 1840 was an innovation. Sheilds’ relationship with Vignoles was evidently significant, as his book is dedicated to his teacher, mentor and employer.

Exactly why Sheilds came to NSW in 1843 is uncertain. He had worked with Vignoles on several British Railways and was probably assured of further work. There was no prospect of furthering his career as a railway engineer in Sydney at that time as there were no railways. The reason for the migration may be related to family as he probably travelled with two sisters, his uncle was the Solicitor-General of NSW, and he was related to Darcy and William Charles Wentworth, leading citizens of the colony.

He found work with the newly formed City Council, eventually as City Surveyor, and it was from this role that he was recruited by the Sydney Railway Company. When Australian railways were first mooted, Earl Grey, Secretary of State for the Colonies, foresaw the possibility of the railways of the several Australian colonies one day meeting at their borders and recommended that a uniform gauge be adopted, and that it should be British standard gauge, and this was agreed. At the time of Sheilds’ appointment in April 1848 there was no railway yet in existence anywhere in Australia, and he reviewed the proposed Sydney railway and recommended that a wider gauge – Irish 5’3”, 1600mm – would be better. The issue was uniformity not the actual width between the rails so Earl Grey and the other colonies, at least Victoria and South Australia and Tasmania, agreed to the change. The subsequent decision by New South Wales to re-visit the issue and change back to standard gauge came after Sheilds had left the colony so the debacle cannot be laid at his feet, but it was his first change which created the opportunity for the reversal and the subsequent decades of mixed gauge and transhipment of goods at border stations.

By the end of 1850 the Sydney Railway Company was particularly short of cash and so its board made significant reductions in the salaries paid to its employees, all of whom consequently resigned. Sheilds left Sydney in early February 1851, at first succeeded by Henry Mais and then James Wallace and it was the latter who made the fateful gauge change for NSW railways. Victoria and South Australia had had enough of New South Wales nonsense, had materials manufactured to the broader gauge in transit, and refused to change again.

Back in England, Sheilds was employed by Vignoles again and worked on several signal projects, perhaps the most relevant to his book being the Crystal Palace. His solutions to the problems he faced designing iron beams and framed girders which a modern engineer might be tempted to call trusses are the core of his text.

Francis Sheilds married Adelaide Baker in 1860 and they had five children, one of whom at least returned to Australia as an Anglican priest and was until 1929 Archbishop of Armidale. In 1877 Sheilds formally changed his surname to Wentworth-Sheilds in honour of his grandmother who had brought him up after his mother had died during his childhood. Sarah Sheilds, née Wentworth, was the stepsister of Darcy Wentworth, father and grandfather of the well-known figures in Sydney history.

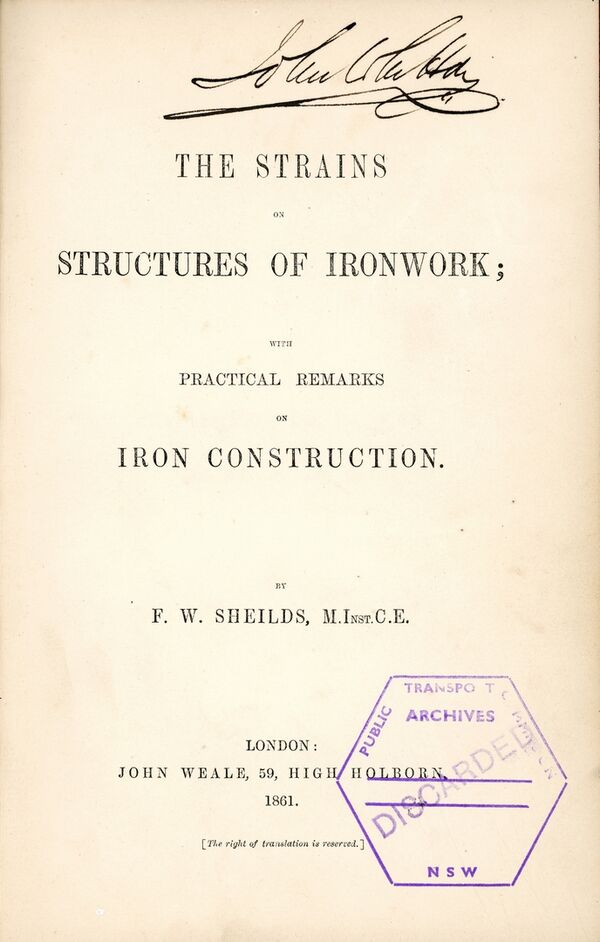

Yet there is an even more compelling reason to ascribe the word amazing to this small book, for the signature of its first owner is inscribed on its title page – this is the personal copy of John Whitton, the Father of the New South Wales Railways. James Wallace announced his intention to resign as engineer before the railway opened in late 1855. Whitton was recruited in England and arrived in Sydney in 1856. Unlike his predecessors Whitton would remain in the role for a long time, more than thirty years, and by the time age and health forced his hand in 1890 the New South Wales railways were built.

So how does an archive in 2020 acquire such a significant volume? Herein lies another tale. The book is marked on the title page with the stamp of the Public Transport Commission of NSW Archives. For any reader not familiar with the cycle of names of the NSW railway operator, PTCNSW was the title in the 1970s. The book was in the official railway archives. Later the State Rail Authority, into which the PTCNSW had morphed, decided to transfer what had previously been an in-house archive to the State Archives and Records Authority. SARA is a dedicated part of the state government establishment which specialises in archiving all records generated by state agencies. SARA was later renamed Museums of History.

At some stage, certainly before the transfer to SARA, a decision was made that Sheilds’ book was not required as part of the archive and so the word ‘DISCARDED’ is stamped over the PTCNSW hexagon. It must be at about this point that Don Hagarty enters the story. Don was an engineer with the NSW Railways, and ultimately the last person to hold the title ‘Chief Civil Engineer’. He was intensely interested in the history of the railway, especially its formative years, and his great work Sydney Railway 1848 – 1857 (464pp) was published by ARHSnsw in 2005. Evidently Don became aware of the disposal of The Strains on Structures of Iron Work, and he took the volume into his extensive library.

Sadly, Don left us in March 2020, aged 90. This author was honoured to deliver a eulogy at the funeral of his friend on behalf of the Society. Don’s collection was bequeathed to ARHSnsw which had been a focus of his life for so long and of which he had long been made a life member. Anyone interested in more detail of the life and work of Francis Webb Sheilds ought to track down a copy of Don’s book. It is no longer in print, but second-hand copies are sometimes available. The unusual surname Wentworth-Sheilds still occurs in telephone directories. Perhaps they identify descendants of F W Sheilds.

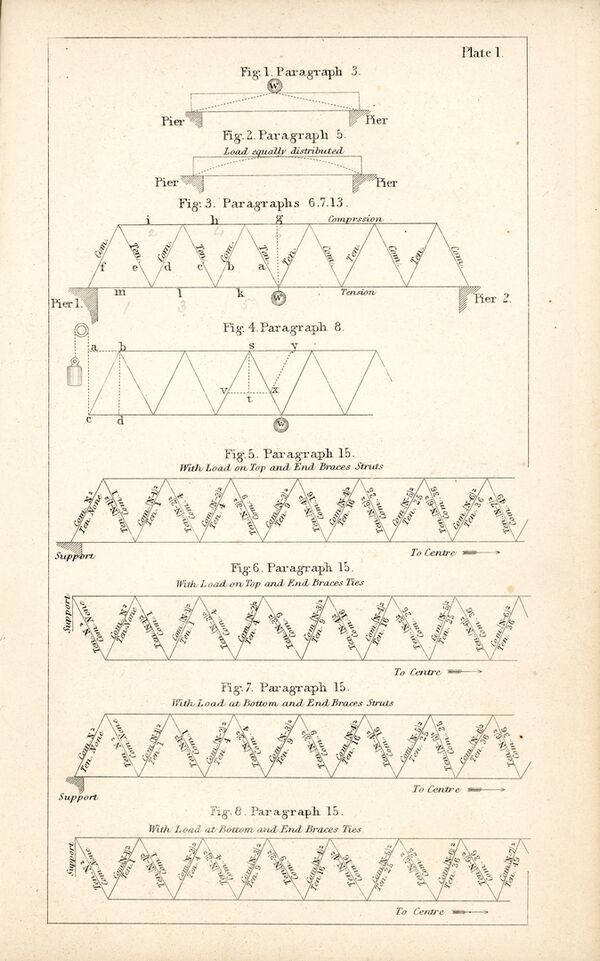

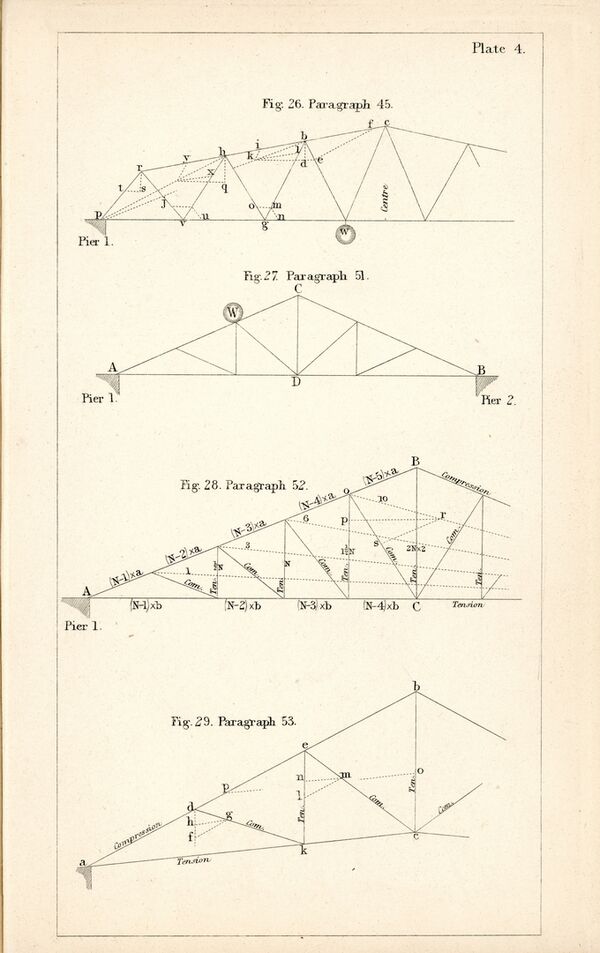

The book treats all girders and what would later be called trusses as a continuum. Starting with the most elementary concept of a simple beam with a central point load, Sheilds analyses ever more complicated spans ending with roof structures which must be considered trusses, though he never uses that word. His analysis is basically one of statics which implies without formal statement that at all joints in a girder fabricated as flanges and web members, the axial forces in the several members are in balance. He makes no mention of redundancy, for while he recommends opposed diagonals in panels where the member intended to carry tensile force needs to be in both directions as a load rolls across the girder, he makes no mention of the potential for their interaction. For highly redundant structures such as lattice girders he treats these as multi-layered (Warren) girders, each statically determinate, juxtaposed and carrying equal shares of the load. In practice of course the flange members are not simply adjacent but the same single iron members. His treatment of plate web girders is necessarily brief for he cannot analyse the web, though he does find them to be ‘excellent’.

In accordance with the age, the ‘Strains’ of the title are what current engineering parlance would call forces. The use of that word to refer specifically to dimensional changes had not yet arisen. The printing technology of the age required the many diagrams to be separate from the text and this is a hindrance to reading, though using two computer screens helped greatly.

One insight which this author gained was in Sheilds’ use of the term ‘Bow and String’, rather than ‘bowstring’ for tied arches. The old terminology seems much more appropriate.

But for £100 of annual salary this erudite man might have remained in Sydney and be accorded a bust on Central station in Whitton’s place. They were born in the same year. Sheilds lived until 1906.

To seeSheilds'book use this link: